Djed A, oil on canvas, 200 x 80 cm, 2022

The Djed column is one of the most iconic and ancient symbols of ancient Egypt. It represents the backbone of the god Osiris and is often associated with stability, strength and resurrection. It is characterized by its four horizontal beams, which are said to represent the four pillars of the universe. The column also features a central shaft that symbolizes the backbone of Osiris. At the top of the column is a capital in the shape of the head of the god Ptah, who was considered the patron saint of craftsmen and artisans.

The Djed column was widely used in ancient Egyptian architecture, both as a decorative element and as a structural support. It can be found in temples and other religious buildings, where it was often painted in bright colors or covered with gold leaf.

The origins of the Djed column are unclear, but it is believed to have been associated with the god Osiris since at least the time of the Old Kingdom (2686-2181 BC). According to myth, Osiris was killed by his jealous brother Set and then resurrected by his wife Isis, who reassembled his body with the help of the Djed Pillar. Over time, the Djed Pillar became an important symbol of stability and continuity in Egyptian culture. It was often used in funerary art, where it was believed to give strength and support to the deceased in the afterlife. It was also used for amulets and other small items that would bring good luck and protection to its owner.

The Djed Pillar is believed to have its origins in a tree-like symbol that was worshipped on the Nile by cultures before the Egyptians, who adopted it. The symbol was known as the tamarisk tree and was associated with the goddess Hathor, who was revered for her power over fertility and regeneration.

The connection between the tamarisk tree and the Djed Pillar illustrates the deep roots of ancient Egyptian culture in the natural world. Like many other cultures, the Egyptians saw the natural world as a manifestation of the divine.

Djed B, oil on canvas, 200 x 80 cm, 2022

The Djed column is one of the most iconic and ancient symbols of ancient Egypt. It represents the backbone of the god Osiris and is often associated with stability, strength and resurrection. It is characterized by its four horizontal beams, which are said to represent the four pillars of the universe. The column also features a central shaft that symbolizes the backbone of Osiris. At the top of the column is a capital in the shape of the head of the god Ptah, who was considered the patron saint of craftsmen and artisans.

The Djed column was widely used in ancient Egyptian architecture, both as a decorative element and as a structural support. It can be found in temples and other religious buildings, where it was often painted in bright colors or covered with gold leaf.

The origins of the Djed column are unclear, but it is believed to have been associated with the god Osiris since at least the time of the Old Kingdom (2686-2181 BC). According to myth, Osiris was killed by his jealous brother Set and then resurrected by his wife Isis, who reassembled his body with the help of the Djed Pillar. Over time, the Djed Pillar became an important symbol of stability and continuity in Egyptian culture. It was often used in funerary art, where it was believed to give strength and support to the deceased in the afterlife. It was also used for amulets and other small items that would bring good luck and protection to its owner.

The Djed Pillar is believed to have its origins in a tree-like symbol that was worshipped on the Nile by cultures before the Egyptians, who adopted it. The symbol was known as the tamarisk tree and was associated with the goddess Hathor, who was revered for her power over fertility and regeneration.

The connection between the tamarisk tree and the Djed Pillar illustrates the deep roots of ancient Egyptian culture in the natural world. Like many other cultures, the Egyptians saw the natural world as a manifestation of the divine.

self, oil on canvas, 60 x 45 cm, 2020

Self shows a close-up portrait of a woman […]. A mask-like painting appears on the face, which makes the hyperrealistic painting appear slightly abstract. The cropping focuses on the face in close-up. The dark green eyes stand out due to the clarity and the naturalistically executed area of the eyes. The plump lips are pursed and form a light kissing mouth. In the picture, David Benedikt Wirth focuses particularly on the makeup contouring, which forms a strong contrast to the natural skin color and the shape of the head. The makeup application consists of a light and dark skin tone. a dark brown line marks the shape of the face and connects the two eyebrows to the nose. Between this graphic-looking marker, a light skin tone is applied to the cheeks and chin. within both eyebrows on the forehead, a light semicircle is formed, emphasizing the upper part of the head. The contouring contrasts with the natural skin color and is reminiscent of the face paint used by indigenous tribes. David Benedikt Wirth discovered this image on the internet as a representative representation of a make-up tutorial. Fascinated by its artificiality and beauty, the artist decided to transfer the motif into painting.

In his art, he is particularly interested in the significance of images in a digital context. Society receives images on a daily basis via social media and other online platforms. in recent years, a new ideal of beauty has emerged through the deliberate presentation of selfies. The public display of the special effect of make-up on the face can greatly change the shape of the face and how it is perceived.

The painting of David Benedikt Wirth is exhibited in the context of the paintings of the New Objectivity in the exhibition at the Museum Haus Opherdicke. It illustrates the cool, objective view of the New Woman in the 1920s, to whom objectivity meant more than flawless beauty. The work self shows an aesthetic, photorealistic rendering of a young woman, borrowed from social media on the internet. The artist’s choice of image and execution revisits the subject and history of painting. Contouring echoes ancient paintings in a profane context and connects past and future.

Text by Wilko Austermann, Arne Reimann from the catalogue Face to Face, Porträts aus der Sammlung Frank Brabant und Gäste

Tethys, oil on canvas, 55 x 90 cm, 2020

The oil painting Tethys shows the head of a life-size goblin shark. Although this shark species has existed unchanged for at least 125 million years, it was only discovered about 120 years ago off Sagami Bay, Japan.

Very little is still known about this species. The exterior of the deep sea shark is reminiscent of a mythical creature or Albrecht Dürer’s depiction of the devil. At the same time, the naturalistic painting conveys a vulnerable side of the creature. Tethys is the name of the primeval ocean in which this shark species already lived.

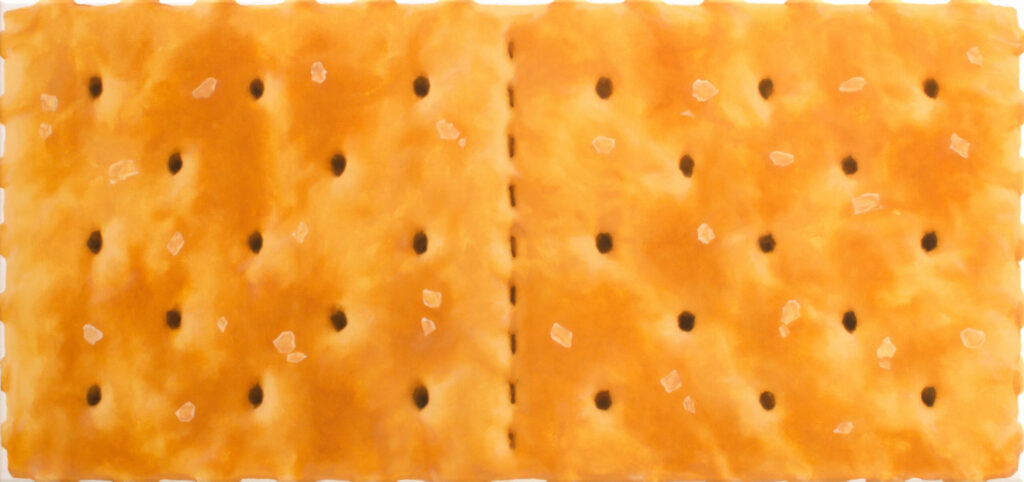

Pack SI1, oil on canvas, 70 x 47 cm, 2018

The series Pack deals with gang clothing and its symbols. The subjects are based on color and black-and-white photographs that were published in the 1970s, among others in New York Times articles. The series examines in its life-size motifs in particular their anthropological and social level, the totemic elements of the symbols, as well as the codes contained in clothing. The oil on canvas technique used combines the materiality of clothing with the raster artifacts of image storage on the same pictorial plane.

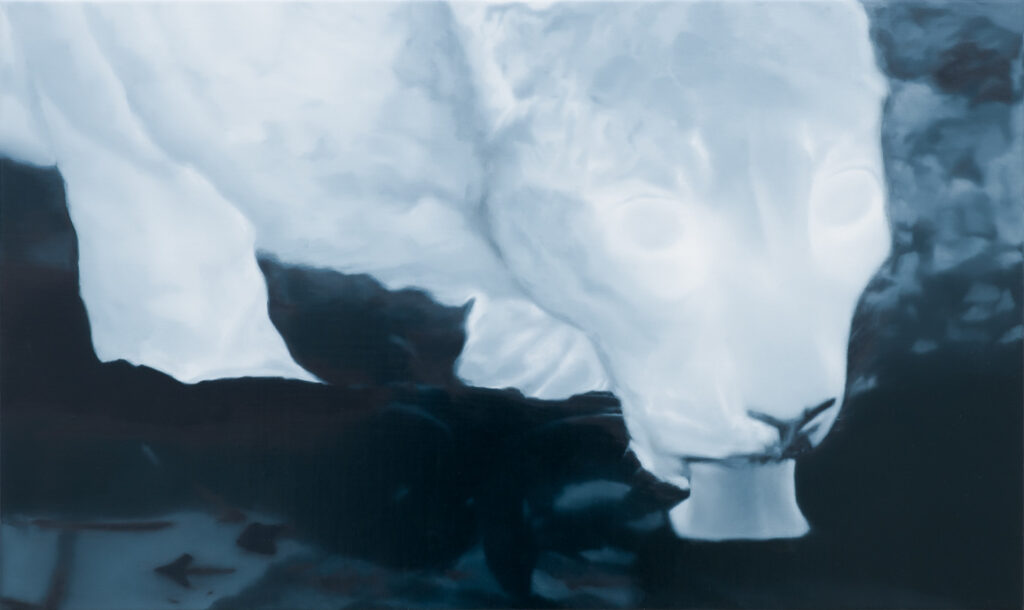

Sekhmet, oil on canvas, 190 x 70 cm, 2021

Among the ancient Egyptians, Sekhmet, who is depicted as a woman with the head of a lioness, was worshipped as a goddess of war, but also as a goddess of protection against disease and of healing. In the myth The Destruction of Mankind it is told how she kills more and more people in a bloodlust in retaliation for their wickedness and can only be put out of action by a ruse of other gods.

In her role, she remains unfathomable to both gods and humans, and as a figure, ambivalent in her worship.

In his painting bearing the name of the goddess, David Benedikt Wirth approaches these ambivalences in brushstroke after brushstroke. He scans the surface of the original ceramics, discovers nuances, reflections, structures, and translates them with painterly means into an astonishingly realistic image that finally confronts the viewer in life-size. The inconceivability of this female figure is reflected in the brilliance of the painterly representation and invites the viewer to discover it layer by layer in all its ambiguity. […]

Text by Tasja Langenbach, jury member of the NRW.Bank.Art prize 2021

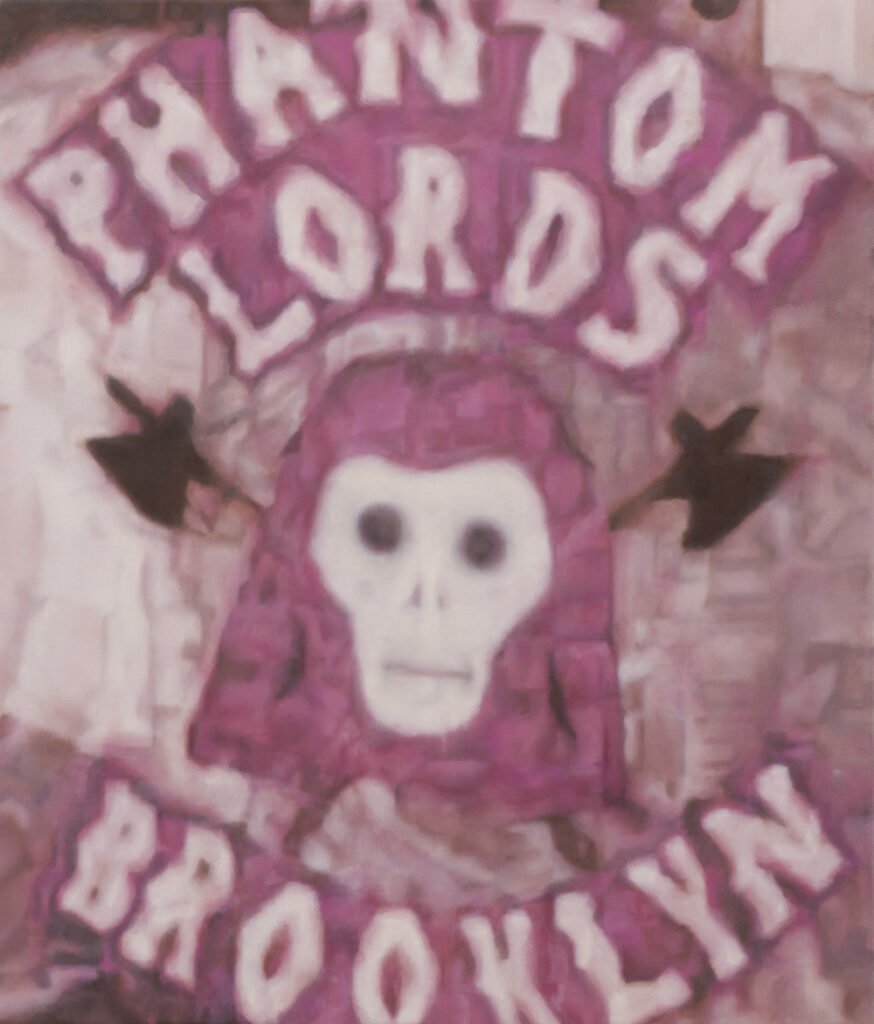

Phantom Lords, oil on canvas, 54 x 46 cm, 2022

The series Pack deals with gang clothing and its symbols. The subjects are based on color and black-and-white photographs that were published in the 1970s, among others in New York Times articles. The series examines in its life-size motifs in particular their anthropological and social level, the totemic elements of the symbols, as well as the codes contained in clothing. The oil on canvas technique used combines the materiality of clothing with the raster artifacts of image storage on the same pictorial plane.

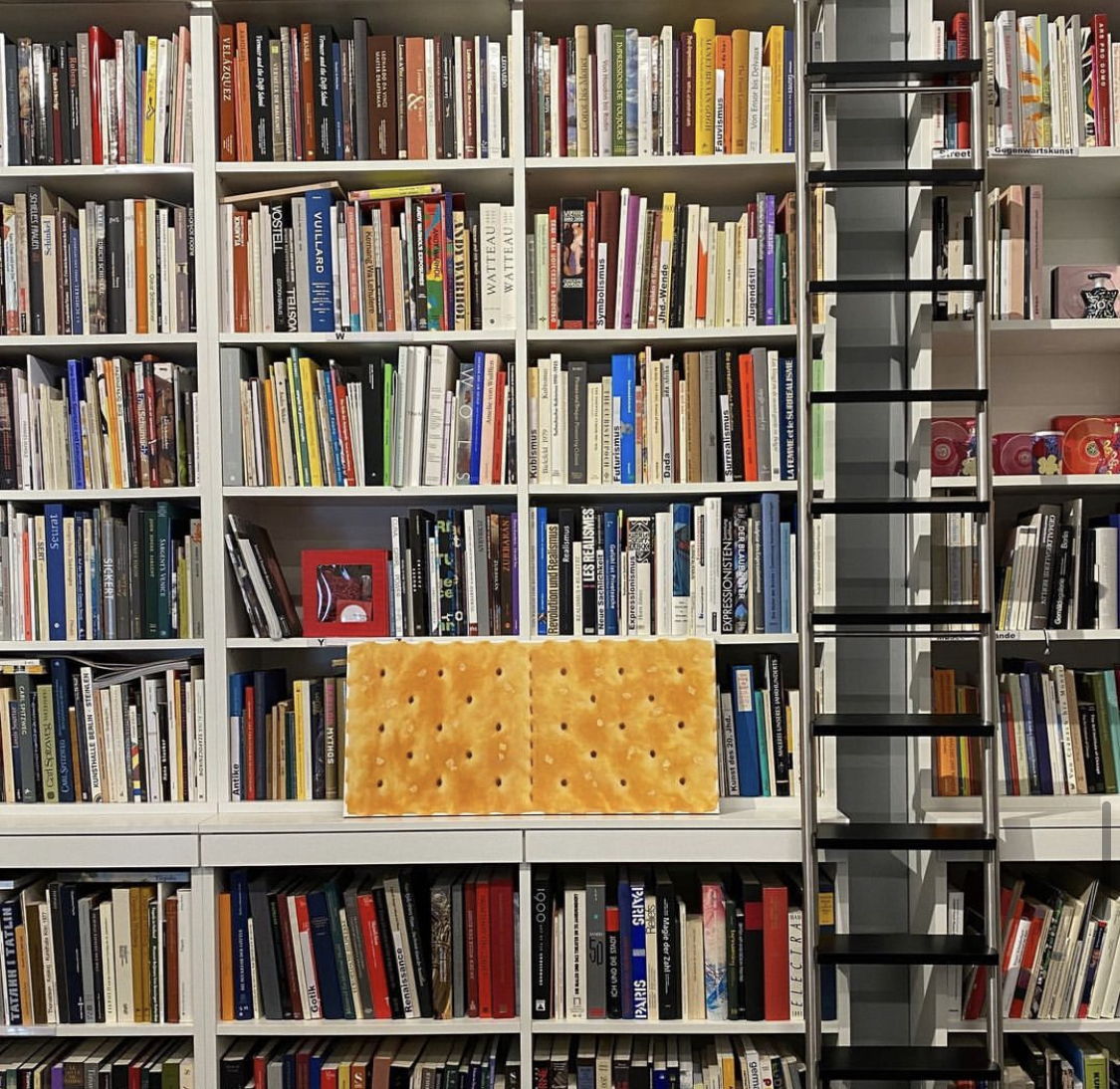

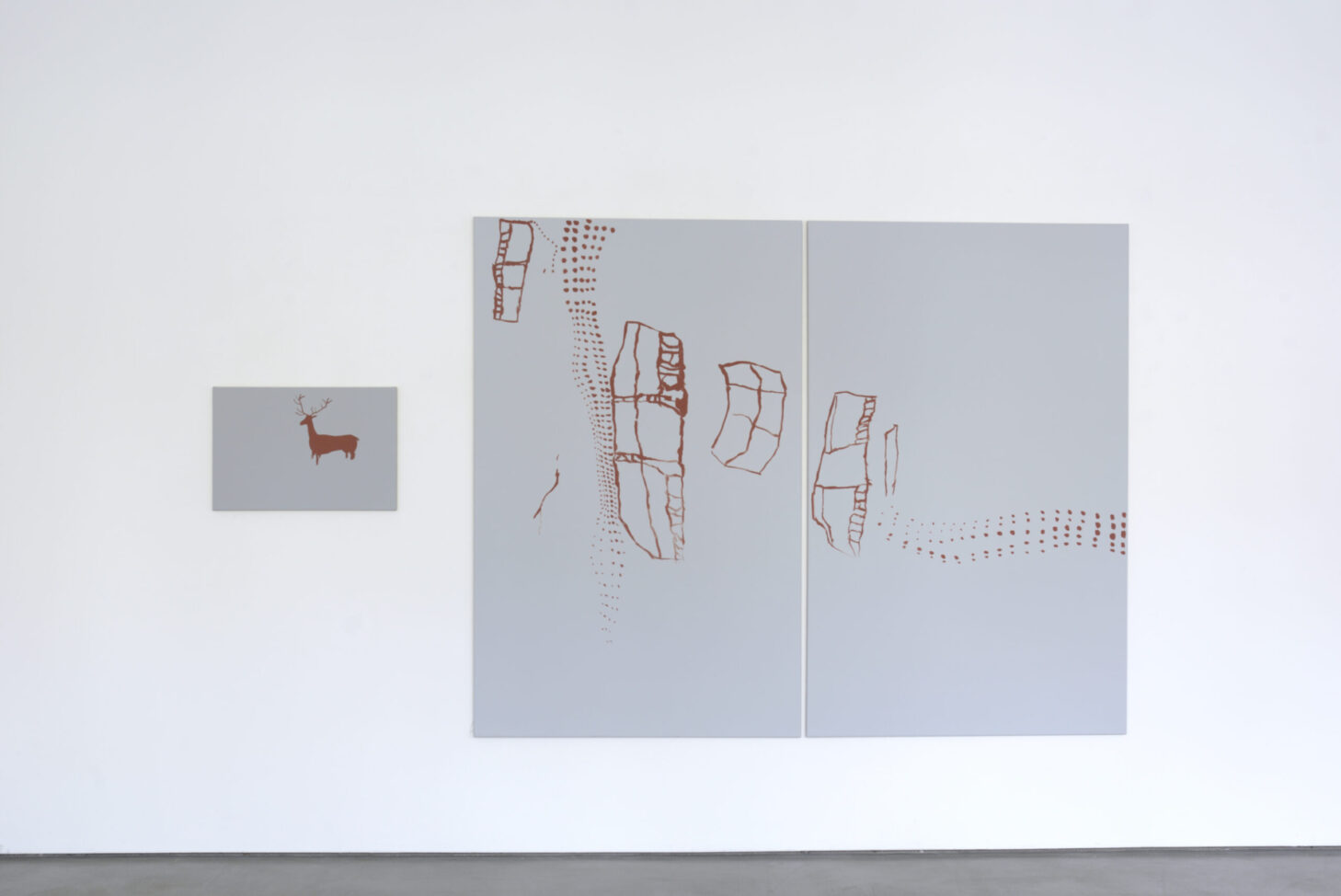

cave (trace), andalusian red ochre, saliva on canvas, diptych, 190 x 245 cm, 2019

In the course of researching the origins of our human culture and a universal human visual language, I came across early, recurring motifs, techniques and interpretations. The Höhle series is primarily inspired by the cave paintings, some 15,000 years old, found in the regions of Valltorta and Cantabria in what is Spain today. Depicted on these are mostly animals, such as deer, reindeer, horses and bulls, as well as numerous symbols that often represented the members of the tribes that left their mark. Despite being over ten thousand years of age, the paintings sometimes seem as if they were applied directly, as if they were created just a short time ago. In addition to the method of application with the brush, this is caused by the very lightfast and stable pigments, which came from the surroundings of the site and were usually ground from earth or plant charcoal. Saliva, resin, animal fat or blood served as binders. The paint was applied with fingers or brushes.

Andalusian red ochre was used for the works in the series. This red, dull luminous pigment was of high spiritual value in the Neolithic period and was used not only for rock painting but also for burial rites.

Only materials common in the Neolithic period were used, such as red ocher, saliva and painting tools made from worked sticks. This technique allows the pigment to shine as purely as it did 15,000 years ago.

The neutral gray ground of the canvas corresponds to the brightness of the cave wall of the site.

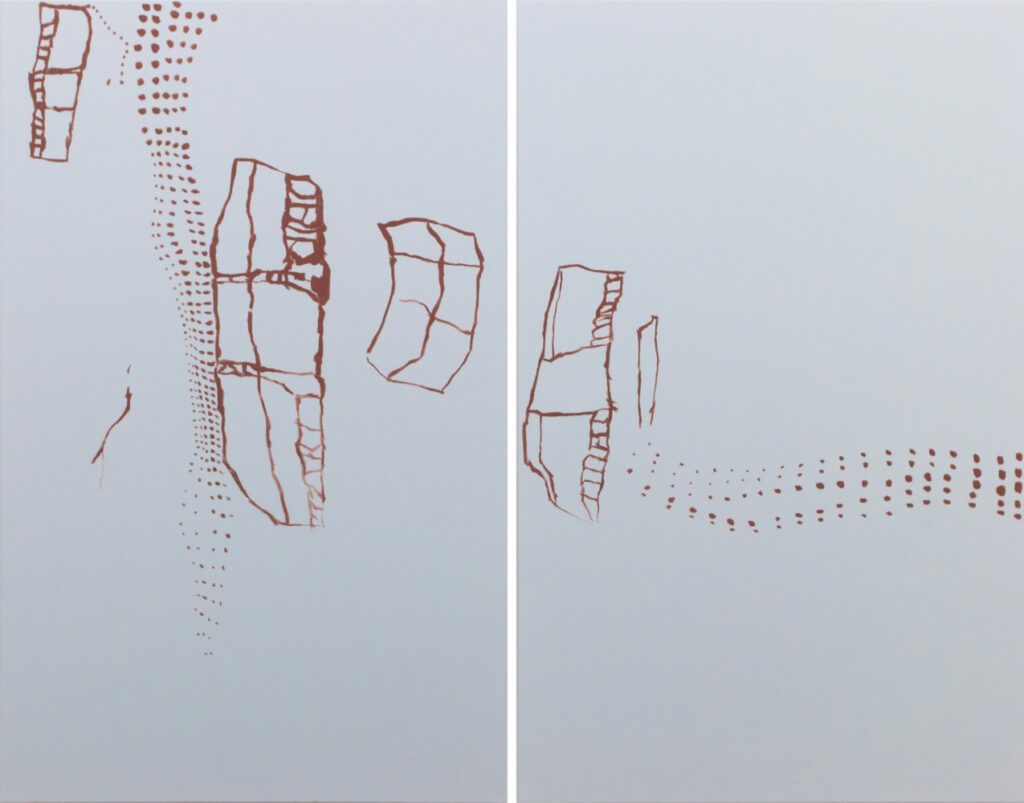

Höhle (Symbole), andalusian red ochre, manganese black, saliva on canvas, 50 x 80 cm, 2019

In the course of researching the origins of our human culture and a universal human visual language, I came across early, recurring motifs, techniques and interpretations. The Höhle series is primarily inspired by the cave paintings, some 15,000 years old, found in the regions of Valltorta and Cantabria in what is Spain today. Depicted on these are mostly animals, such as deer, reindeer, horses and bulls, as well as numerous symbols that often represented the members of the tribes that left their mark. Despite being over ten thousand years of age, the paintings sometimes seem as if they were applied directly, as if they were created just a short time ago. In addition to the method of application with the brush, this is caused by the very lightfast and stable pigments, which came from the surroundings of the site and were usually ground from earth or plant charcoal. Saliva, resin, animal fat or blood served as binders. The paint was applied with fingers or brushes.

Andalusian red ochre was used for the works in the series. This red, dull luminous pigment was of high spiritual value in the Neolithic period and was used not only for rock painting but also for burial rites.

Only materials common in the Neolithic period were used, such as red ocher, saliva and painting tools made from worked sticks. This technique allows the pigment to shine as purely as it did 15,000 years ago.

The neutral gray ground of the canvas corresponds to the brightness of the cave wall of the site.

predator 2, oil on canvas, 57 x 70 cm, 2022

The work depicts a photograph taken by a thermal imaging camera. The subject is a close-up of a cat’s head. The familiar appearance of a cat is shifted into a different spectrum of light. This shift questions our viewing habits as humans and represents an extension of our perceived unambiguous reality.

Some animal species, such as vipers have the ability to perceive parts of the infrared spectrum in order to hunt at night. Humans do not possess this ability and have developed devices to compensate for this incapacity. Does the title predator 2 refer to the cat, or is the cat being observed by another predator?

ecto, oil on canvas, 44 x 60 cm, 2022

The work ecto shows a photo taken with a thermal imaging camera. The subject is a closeup of a human hand with a gecko on it. The work contrasts the ectothermic, cold-blooded reptile with the hand of the endothermic human. The longer the gecko is on the hand, the more it takes on the body temperature of humans.

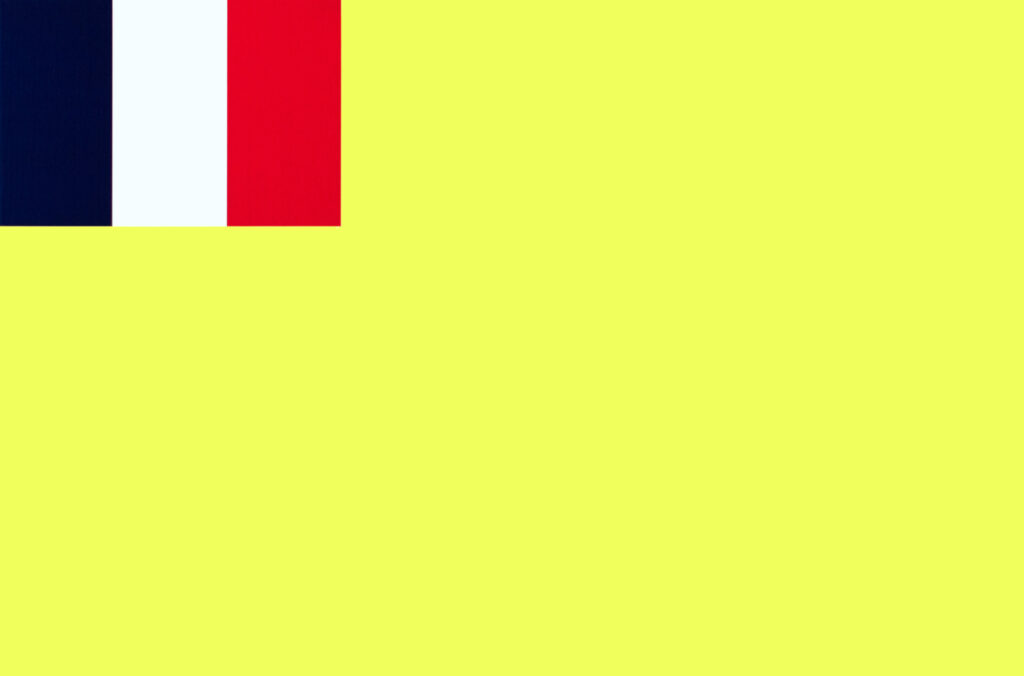

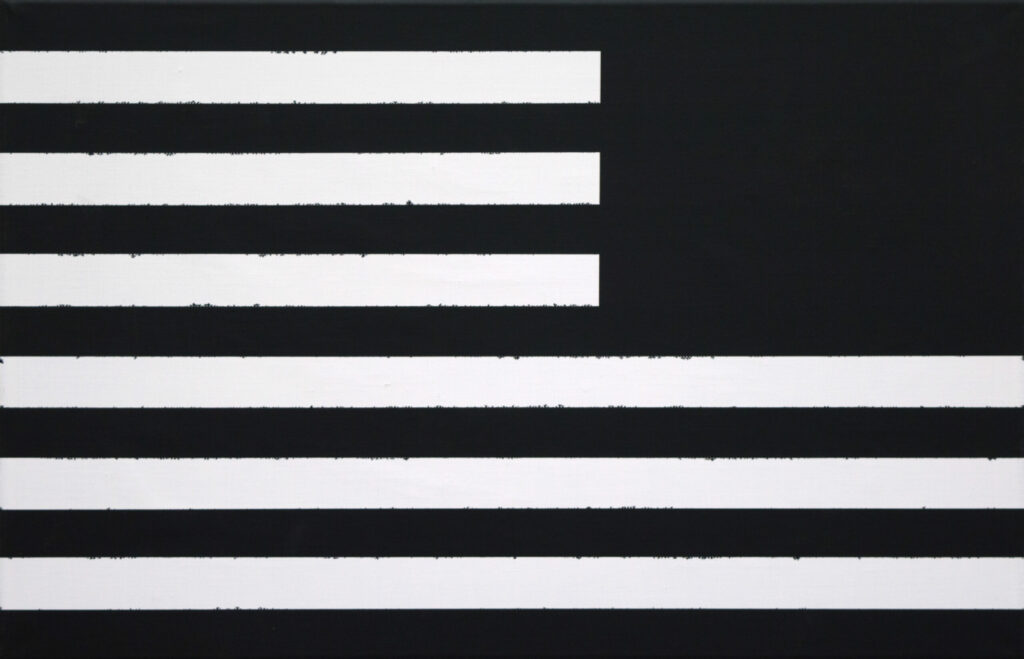

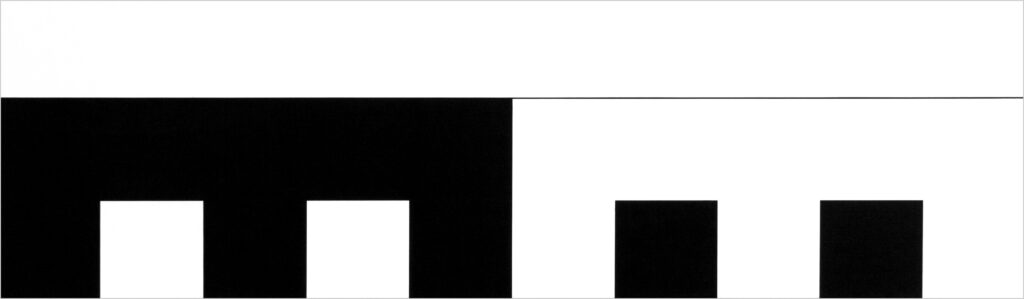

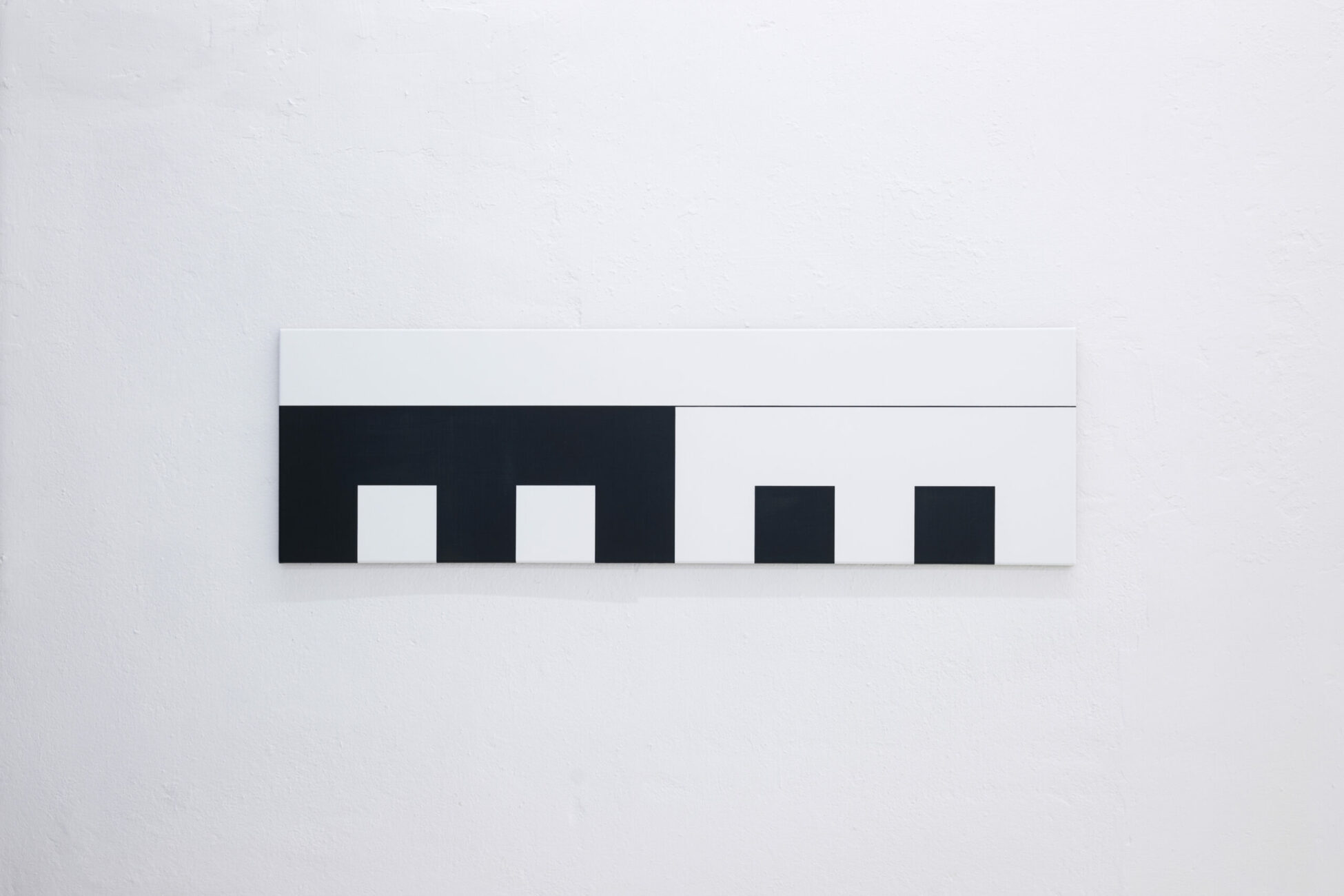

priority scheme, acrylic on canvas, 44 x 68 cm, 2016

The flag of the United States of America has become a relevant, ubiquitous and diversely viewed icon through the history of its country, its role in international politics, economics and culture. Despite the United States’ Flag Code, which specifies how the U.S. flag is to be handled and thus prohibits, among other things, altering its appearance, so-called subdued versions have been developed for the use on military uniforms and vehicles.

These flags deviate from the official flag of the United States, with its seven red and six white horizontal stripes, and a blue canton studded with 50 white stars on the left side, and are color-matched to the particular camouflage pattern on which they are used (see mode).

By using the subdued versions the soldier‘s visibility and exposure are reduced, thus increasing his efficiency.

Furthermore, when the flag is placed on the right side, such as on the upper arm of a U.S. soldier, a mirrored version is used, called the Reverse Field Flag, since the flag code also requires the flag to fly canton first, in the direction of running or travel on its wearer, to avoid the otherwise possible association of a retreat by compositional means.

One can say that the modification of the U.S. flag is for the sake of perceptual and psychological optimization in its environment, which has a higher priority here than the integrity of the icon. The works of the priority series deal with this phenomenon, as well as the diverse consideration of symbols. Their size ratio to each other, was adjusted to their perceived density of information.

priority scheme, Despite its mirrored, starless composition and its implementation in black acrylic paint, which covers only a little more than half of the white primed canvas, it is possible to speak of a U.S. flag in the impression. This flag painting was not made from an aesthetic point of view, but with efficiency in mind, based on good legibility along with a low effort of production.

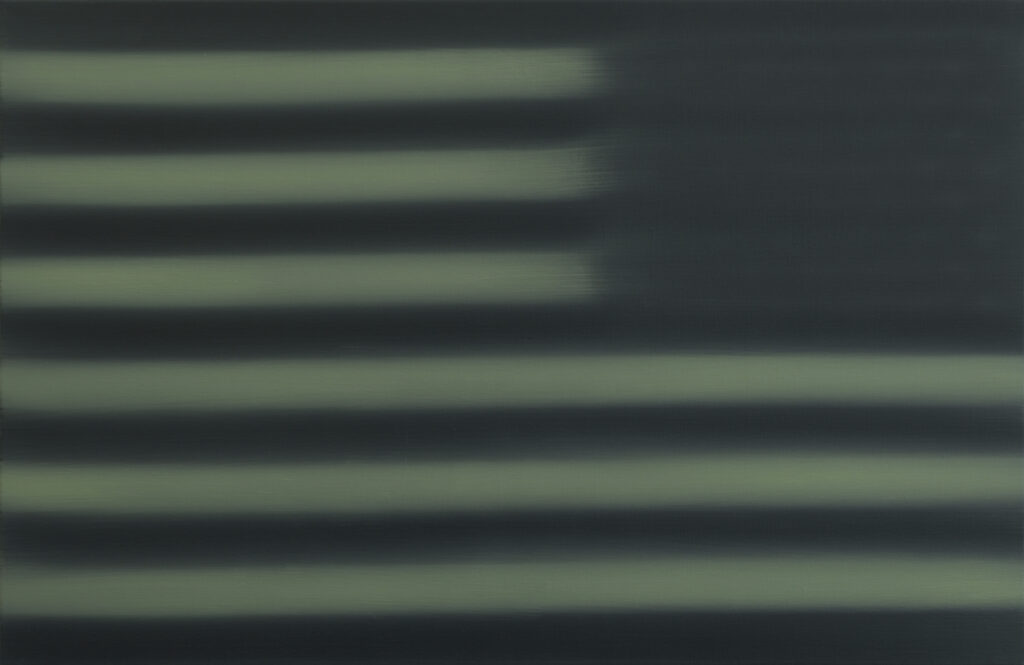

priority B, oil on canvas, 55 x 77 cm, 2018

The flag of the United States of America has become a relevant, ubiquitous and diversely viewed icon through the history of its country, its role in international politics, economics and culture. Despite the United States’ Flag Code, which specifies how the U.S. flag is to be handled and thus prohibits, among other things, altering its appearance, so-called subdued versions have been developed for the use on military uniforms and vehicles.

These flags deviate from the official flag of the United States, with its seven red and six white horizontal stripes, and a blue canton studded with 50 white stars on the left side, and are color-matched to the particular camouflage pattern on which they are used (see mode).

By using the subdued versions the soldier‘s visibility and exposure are reduced, thus increasing his efficiency.

Furthermore, when the flag is placed on the right side, such as on the upper arm of a U.S. soldier, a mirrored version is used, called the Reverse Field Flag, since the flag code also requires the flag to fly canton first, in the direction of running or travel on its wearer, to avoid the otherwise possible association of a retreat by compositional means.

One can say that the modification of the U.S. flag is for the sake of perceptual and psychological optimization in its environment, which has a higher priority here than the integrity of the icon. The works of the priority series deal with this phenomenon, as well as the diverse consideration of symbols. Their size ratio to each other, was adjusted to their perceived density of information.

Depending on the viewing angle, the impression of the blurred painted flag changes. While the stars are barely visible from the front, a glance from the side reveals clear contours. The depiction of the flag is not definite, but holds several truths.

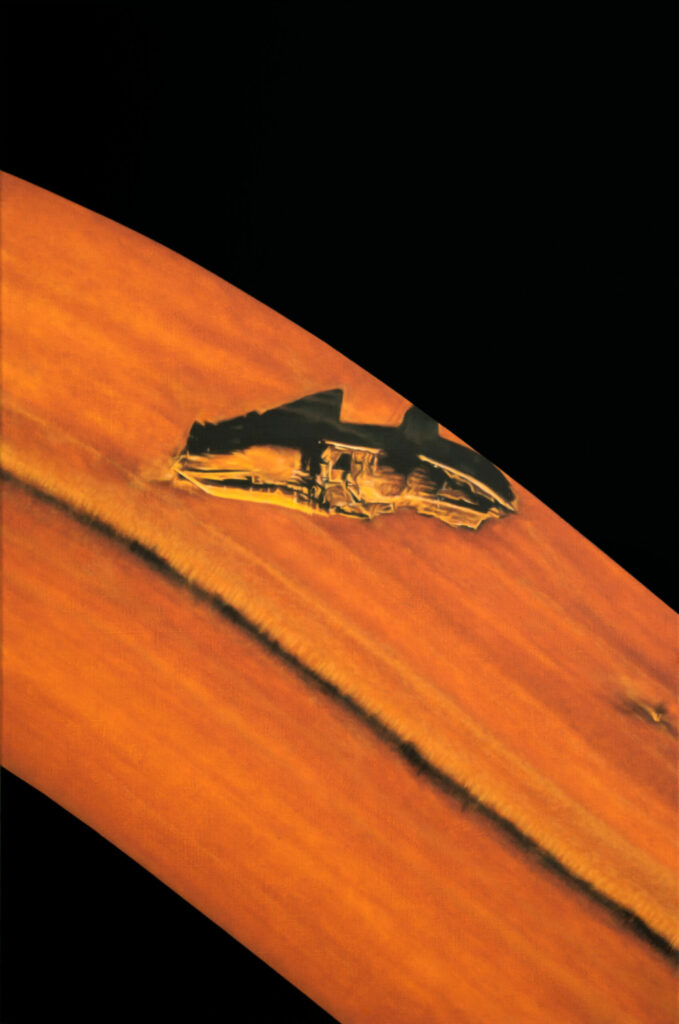

Sonogramm C, oil on canvas, 38 x 40 cm, 2019

The Sonogramm series turns scans of the ocean floor, which are taken by a buoy using side scroll sonar, into paintings. These visualizations, created only from the acoustic reflections, capture the depths of the ocean without its constant darkness being disrupted by light. The precise scanned area is recreated on an orange-yellow spectrum through the means of technology and is surrounded by an undefined black area.

The method of Side Scroll Sonar is based on echolocation, which is used by many marine organisms for orientation. Although life on our planet originated in the ocean, humans rely on perceptual-physiological substitutes to replace their own visual experience of the ocean floor and its depths. The technology necessary for this developed as part of our culture.

The eternal vastness of the unfathomed sea floor is unveiled in some places by high-resolution scans. In the works of the series, the undefined surrounding area, executed with black pigment, forms a single virtual surface. This is juxtaposed with the scan‘s defined area.

An important distinction is particularly visible at the interface between the black surrounding area and the parts with the least reflections and thus the least revealing information, the acoustic shadow, which was painted with deep brown Van Dyck pigment.

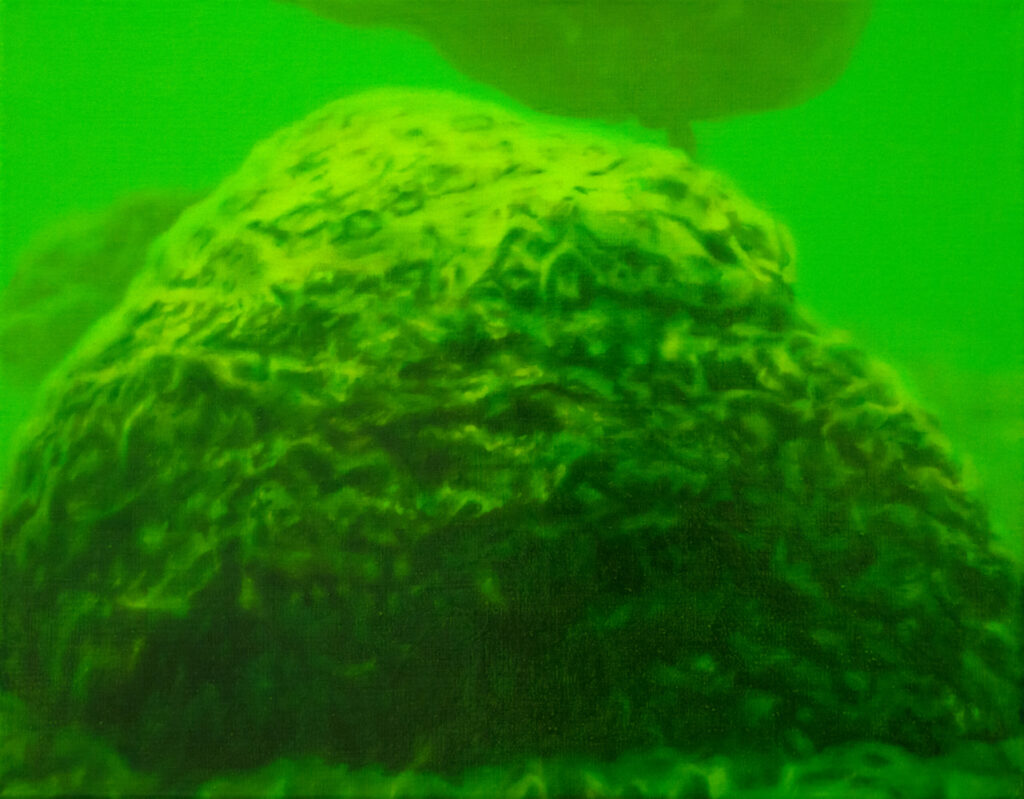

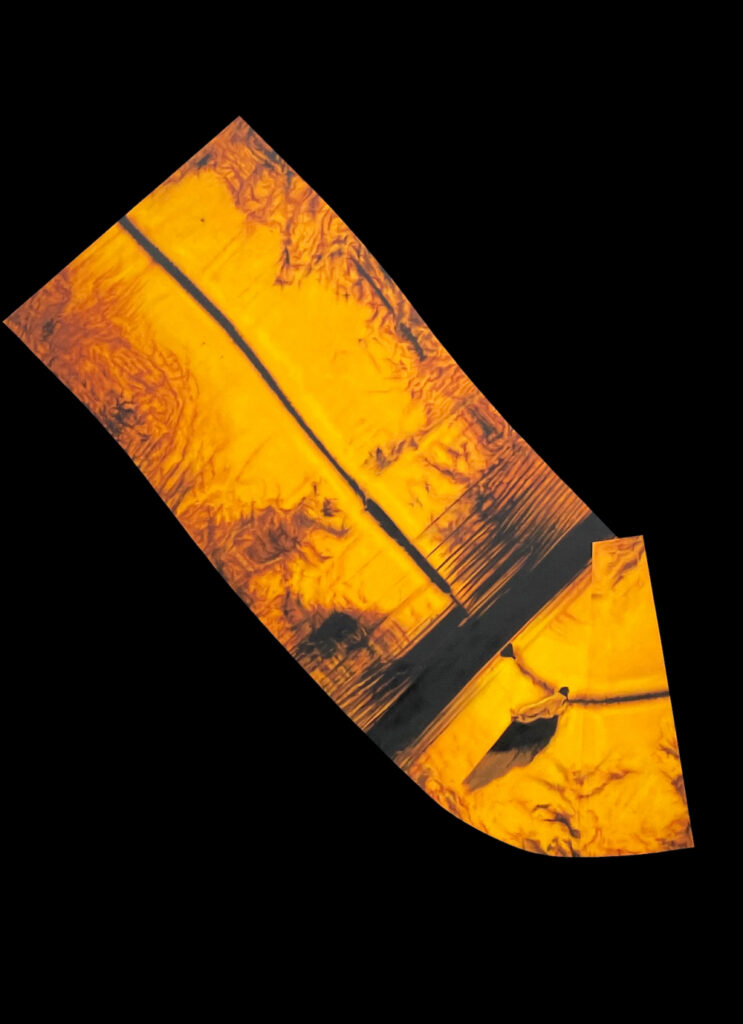

Sonogramm B, oil on canvas, 200 x 145 cm, 2021

The Sonogramm series turns scans of the ocean floor, which are taken by a buoy using side scroll sonar, into paintings. These visualizations, created only from the acoustic reflections, capture the depths of the ocean without its constant darkness being disrupted by light. The precise scanned area is recreated on an orange-yellow spectrum through the means of technology and is surrounded by an undefined black area.

The method of Side Scroll Sonar is based on echolocation, which is used by many marine organisms for orientation. Although life on our planet originated in the ocean, humans rely on perceptual-physiological substitutes to replace their own visual experience of the ocean floor and its depths. The technology necessary for this developed as part of our culture.

The eternal vastness of the unfathomed sea floor is unveiled in some places by high-resolution scans. In the works of the series, the undefined surrounding area, executed with black pigment, forms a single virtual surface. This is juxtaposed with the scan‘s defined area.

An important distinction is particularly visible at the interface between the black surrounding area and the parts with the least reflections and thus the least revealing information, the acoustic shadow, which was painted with deep brown Van Dyck pigment.

Sonogramm A, oil on canvas, 120 x 80 cm, 2018

The Sonogramm series turns scans of the ocean floor, which are taken by a buoy using side scroll sonar, into paintings. These visualizations, created only from the acoustic reflections, capture the depths of the ocean without its constant darkness being disrupted by light. The precise scanned area is recreated on an orange-yellow spectrum through the means of technology and is surrounded by an undefined black area.

The method of Side Scroll Sonar is based on echolocation, which is used by many marine organisms for orientation. Although life on our planet originated in the ocean, humans rely on perceptual-physiological substitutes to replace their own visual experience of the ocean floor and its depths. The technology necessary for this developed as part of our culture.

The eternal vastness of the unfathomed sea floor is unveiled in some places by high-resolution scans. In the works of the series, the undefined surrounding area, executed with black pigment, forms a single virtual surface. This is juxtaposed with the scan‘s defined area.

An important distinction is particularly visible at the interface between the black surrounding area and the parts with the least reflections and thus the least revealing information, the acoustic shadow, which was painted with deep brown Van Dyck pigment.